Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 12

Click on a musical example for playback

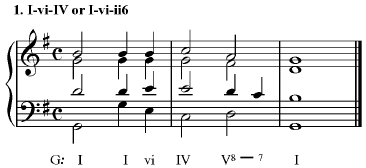

I moving to IV via a stopover on vi is a frequent and beautiful progression. One strong point is the ability to share ^3 between the two chords in the soprano. It is also an easy progression to voice-lead, given the common tones between I-vi, and between vi-IV.

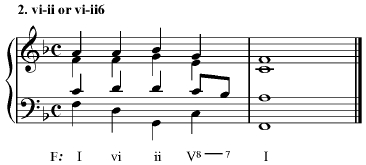

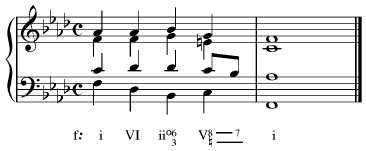

The progression works equally well with ii6 instead of IV.

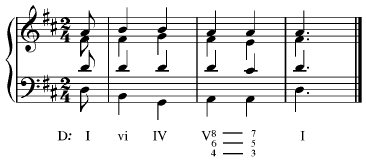

Another soprano motion between I and vi is ^5-^6, which can produce an interesting effect, as in this example.

Perhaps the paradigm, or signature progression, for I-vi is “God Save the Queen”, aka “My Country ‘Tis of Thee”.

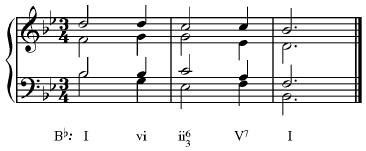

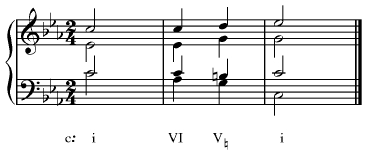

VI works well in partnership with ii, given that they are a fifth apart—the strongest relationship. Because of this, a progression such as this is exceptionally final-sounding and balanced.

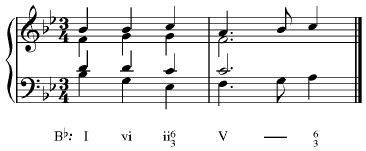

A similar, but not quite as intense, strength can be acquired by using ii6 instead of ii as the goal of vi. Note that this is the only option if you are writing this progression in minor. Why?

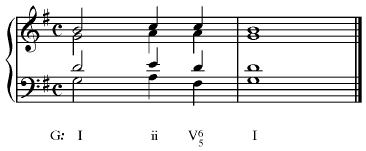

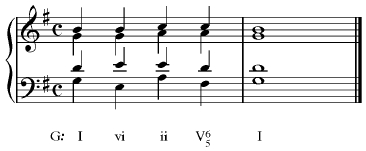

Another handy use of vi is to break up parallels that occur naturally when moving from I to ii. In this example, the opening motion is distinguished by having parallel fifths and parallel octaves.

The interpolation of vi between I and ii solves the problem. This use of a triad is called a voice-leading corrective. It will be covered in some detail in Chapter 16, but it’s worth mentioning here as well.

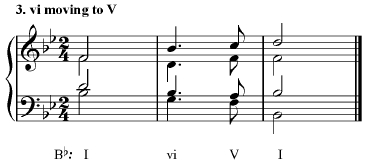

As a predominant chord, vi is quite well suited to motion downwards to V. Remember that from vi to V is motion between two adjacent root-position chords, and therefore voice-leading trouble awaits. In this example, the 3rd of vi is doubled: you will find that this is frequently the best solution to voice-leading problems in this progression.

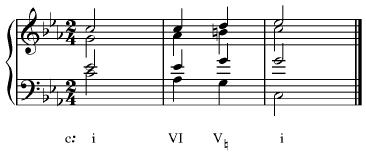

In minor keys, you need to be especially careful with vi moving to V. It is critical to ensure that ^6 (the root of vi) is not in the same voice as ^7 (the 3rd of V) or else an augmented second will result—as is the case here.

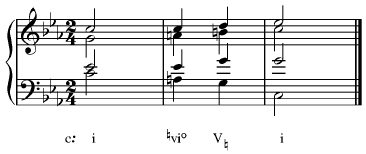

Attempting to repair the augmented second can lead to problems. If you attempt the repair by raising ^6 (much as you might do with IV), you will discover that you have created a diminished submediant chord—quite disagreeable, and not an acceptable sonority by a long shot.

And yet there are parallels lurking everywhere, it would seem. In this example, the augmented second has been repaired, but now there is yet another error in the progression. Where and what is it?

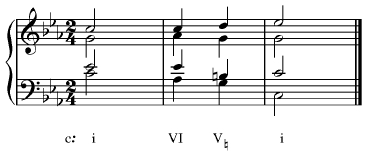

Thus the wisdom of doubling the 3rd of vi is revealed: if you double the 3rd, you won’t wind up in the kind of Catch-22 situation that is shown above. Note also in this example the modification of the tonic triad in order to accommodate the chord construction change on VI.

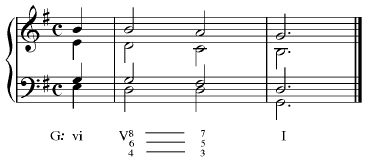

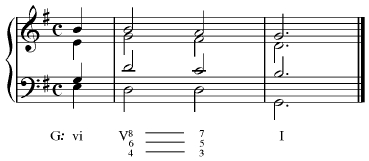

Moving to a cadential 64 can be tricky. In this example, there are parallel octaves moving from vi to the cadential 64.

This is probably the best solution, which retains the generally-advised practice of doubling the root of the cadential 64.

This is a less standard, but nonetheless perfectly acceptable solution, which doubles the 6th of the cadential 64.

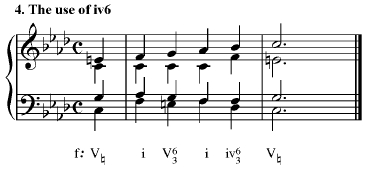

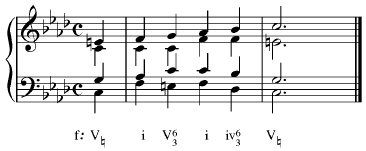

This is the “signature” use of iv6, which is to create a half-cadence with V in minor. Because the semitone motion in the bass is reminiscent of the kinds of cadences that might be encountered in works written in the Phrygian mode, the progression is called a Phrygian cadence. However, it has nothing to do with the Phrygian mode per se. It can be thought of as a special flavor of half cadence.

The voice-leading in the above example is the standard: double the 3rd of iv6. However, this voicing allows for doubling the root of iv6. Bach’s practice prefers the above version.

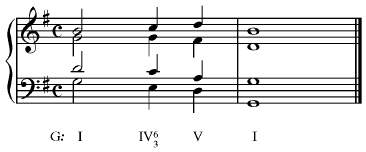

In major, the effect of IV6 leading downwards to V is far less dramatic than in minor, and is not used for a half-cadence in minor as a rule. Note here that IV6 is acting like a plain old predominant chord; the submediant could just as easily be in this location, in fact.

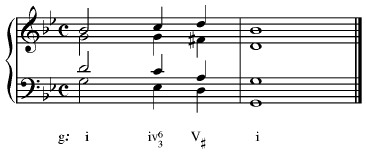

The same progression works just fine in minor. Note that this is not a Phrygian cadence: it is an imperfect authentic cadence. The iv6 is merely approaching V, which then resolves to the tonic as it should. Remember that a Phrygian cadence is by definition a half cadence.