Aldwell-Schachter Chapter 14

Click on a musical example for playback

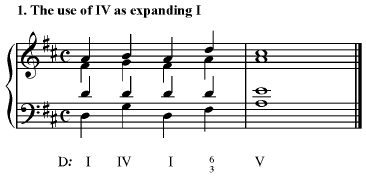

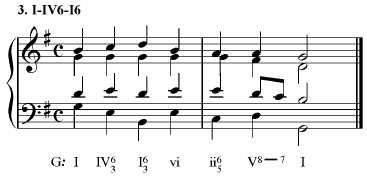

IV shares ^1 with the tonic and can be used to expand I rather nicely. This example is typical of such expansions—note the common tone ^1 in the tenor voice throughout the first measure. The figure ^5-^6-^5 is also typical of this progression. In such progressions, the net effect is a single long tonic chord.

In addition to expanding I, IV can also expand I6. In this progression the common tone is placed in the alto, with a similar soprano line to the preceding example.

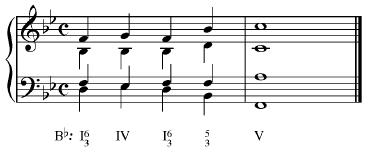

The common tone can also be placed in the soprano, although probably this shouldn’t be done frequently in order to avoid an unnecessarily static soprano (the “Johnny One-Note” school of composition.)

Although this example skips ahead a bit to material from a later chapter, it’s worth noting here that using the IV in its second inversion (IV6/4) allows the bass to retain the common tone throughout, creating what is called a neighboring 6/4. This perhaps more than any other example shows how the net effect of using IV as an expansion is really just a prolonged tonic.

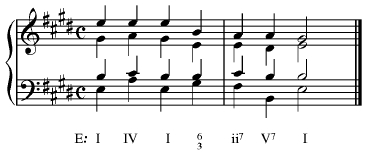

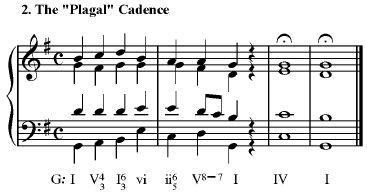

Cadences employing the subdominant rather than the dominant are called “plagal” cadences. (The term plagal is often used to mean “nonstandard”.) Because IV is not particularly conclusive in a cadence, as a rule a plagal cadence follows an authentic cadence (although there are exceptions—see the Chopin example on page 194 of the 3rd edition.) This is example is a signature use of a plagal cadence, as the “Amen” at the end of a hymn.

This particular progression is idiomatic in that it is the result of usage and custom. The soprano outlines ^3-^4-^5 while the bass drops down from ^1 to ^3, via ^6 along the way. The signature use is the last movement of Haydn Symphony No. 101 in D Major (“Clock”) which is given as example 13-7 on page 195 of the 3rd edition. Note that this progression really doesn’t work in any other manner than this—you can’t move upwards easily or even change the interior voicing all that easily.

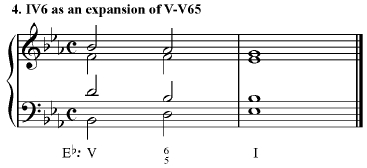

The first example here shows V moving to V65 on its way to a tonic.

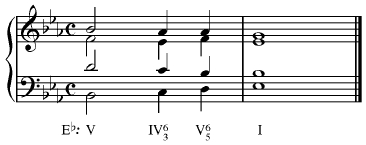

Here a IV6/3 is interposed between V and V6/5. This is a good example of a passing chord, in that it results really more from contrapuntal motion than harmonic considerations. For all practical intents and purposes, the IV6/3 is without function—in fact, you could systematically omit each note of the chord without effecting the overall progression in any way. Although this is the first time this has been presented, be advised that a 6/3 chord can usually be interposed between many pairs of chords corresponding to V-V6/5, such as ii7-(I6/3)-ii6/5.

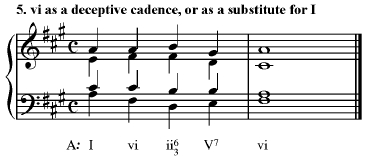

The “deceptive” cadence is so called due to setting up a standard authentic cadence, and then making use of the two common tones between I and vi to move to vi instead of I. This should never be used for a final cadence—assume that my example is part of a larger composition.

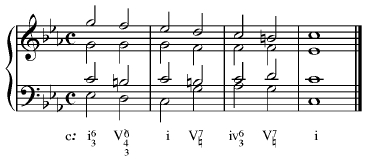

It is also possible to use IV6/3 in the place of vi in a deceptive cadence. This usage here is both an example of a deceptive cadence (downbeat of measure 3) and also shows an expansion of V7 via the iv6/3. Try the same progression with I in the place of iv6/3 and notice how much more static is has become.

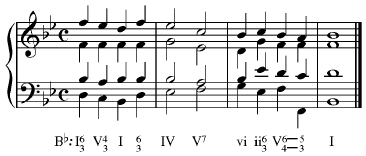

Deceptive cadences are typically used to expand a phrase. Here the final cadence which was expected on the downbeat of measure 3 is delayed by another measure by the use of a deceptive cadence instead of an authentic cadence at this point.